This Week's Finds in Genomic Life

Interesting omics and omics-adjacent reading for your weekend.

1. Virtual Seminars on functional genomics of genetic variants

The University of Washington’s Center for the Multiplex Assessment of Phenotype (CMAP) has an excellent YouTube channel featuring virtual seminars presented by early-career scientists working at the cutting edge of this field. If you’re interested in the latest technologies assess human genetic variants at scale, check out this series. (And if you’d like to present your work, find out more at the series page.)

The most recent seminar is presented by Raquel Cuella Martin of McGill University, on using base editor technology for deep mutagenesis in situ:

2. AI in the life sciences: The Big Picture

This one is from back in April, but Scripps scientist Eric Topol recorded a fascinating interview with Aviv Regev, possibly one of the highest-energy genome scientists working in the field today. The interview is up on Topol’s superb Ground Truths substack. Regev was formerly at the Broad Institute and now is Executive Vice President of Research and Early Development at Genentech. She talks about how major progress in the biomedical sciences depends critically not only on biologists, but on computer scientists, chemists, etc. This isn’t a surprise to anyone, but it does cause some friction at times. Regev says we need to embrace the interdisciplinary nature of the field and we all “should feel very comfortable talking with an accent,” meaning the accent of the field we trained in:

The third point that I think is really material, I often say that when I'm getting asked, everyone should feel very comfortable talking with an accent. We don't expect our computational scientists to start behaving like they were actually biology trained in a typical way all along, or chemists trained in a typical way all along and by the same token, we don't actually expect our biologists to just embrace wholeheartedly and relinquish completely one way of thinking for another way of thinking, not at all. To the contrary, we actually think all these accents, that's a huge strength because the computer scientist thinks about biology or about chemistry or about medical work differently than a medical doctor or a chemist or a biologist would because a biologist thinks about a model differently and sometimes that is the moment of brilliance that defines the problem and the model in the most impactful way.

3. Souped-up CRISPR/Cas9: iGeoCas9

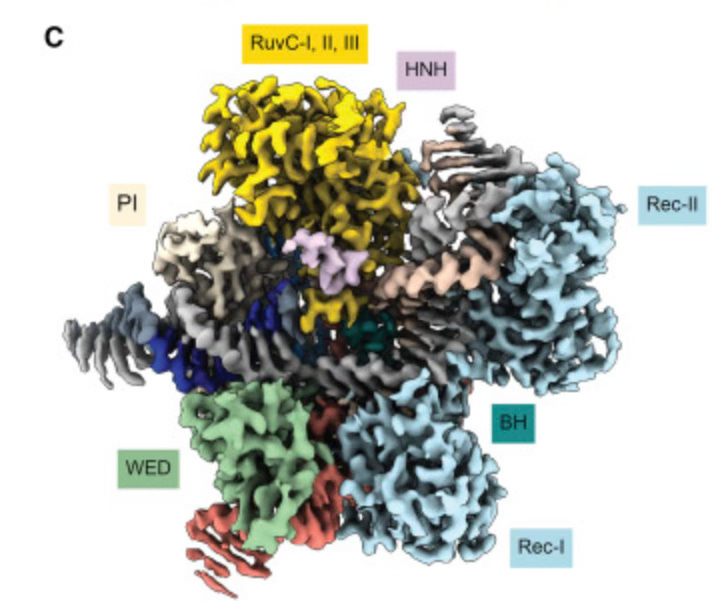

You can’t really overstate the impact of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology on biomedical sciences, but it’s no secret that the technology’s editing efficiency is still not high enough for many envisioned applications, particularly in vivo human editing. Many groups are actively working on improved CRISPR-based editors, including Nobel laureate and CRISPR/Cas9 discoverer Jennifer Doudna. In the latest issue of Cell her group presents a study of Geobacillus stearothermophilus Cas9, or what they call GeoCas9. (The original technology was developed with Cas9 from Streptococcus thermophilus.) GeoCas9 in its wild-type form is inactive in human cells. Doudna’s group evolved a much more potent form of the enzyme, which they call iGeoCas9. (The “i” stands not for “internet”, but “improved”. In the same spirit, I should start calling my weekend cocktails “iCocktails”).

The scientists show that the new version gains its potency from its ability to accelerate the unwinding of double-stranded DNA, a necessary step before the enzyme can cleave DNA. This work is important not so much for iGeoCas9 itself, but rather because there is now a clear target activity and protein domain of Cas9 that can be optimized to generate more efficient editing.

Cryo-EM structure of iGeoCas9, Figure 1C from Eggers, et al. Cell 187:P3249-3261.E14.

4. Philosopher of Biology Peter Godfrey-Smith on Animal Senses

That our senses aren’t a simple window to the world is one of the most important ideas in science (and one that dates back at least to the Scientific Revolution). As we look at our surroundings, our brains construct the images in our heads from the raw input of our visual system. This fact has generated a huge amount of philosophical discussion about what kind of access we have to the external world and how trustworthy our senses are.

But when you consider the physical specs of senses across the animal world, you find capabilities to sense light, sound, smell, electric fields, etc. with astonishingly high sensitivity, often bumping up against the limits of what is physically possible. The abilities of animal senses, suggests philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, should make one ask whether philosophical doubts about the reliability of our perceptions might be overstated:

On the one hand, perception is said to be controlled hallucination; on the other, we find astounding sensitivity in animals to what is around them. There is not an outright contradiction between the two views. The people who think we are perceiving a model or simulation do say that these simulations are constrained by stimuli from outside. They might now add that the models we experience are constrained in very precise ways by these influences…

But there does seem to be at least some incongruity here. Perhaps a better overall picture will recognize the active, constructive nature of perception without cutting us off from the objects around us. While our brains do not simply mirror the world, animals—nonhuman and human—are exquisitely embedded, suspended, in nature’s energies.

This comes from an New York Review of Books excellent review of two books on animal senses by Ed Yong and Jackie Higgins. (Register for a free NYRB account to read the piece.) Godfrey-Smith himself is the author of a fascinating book, Other Minds, on the minds of cephalopods.

Have a great weekend.