Darwin and The Cultural Rise of Science

An appreciation of The Voyage of the Beagle to celebrate Darwin Day.

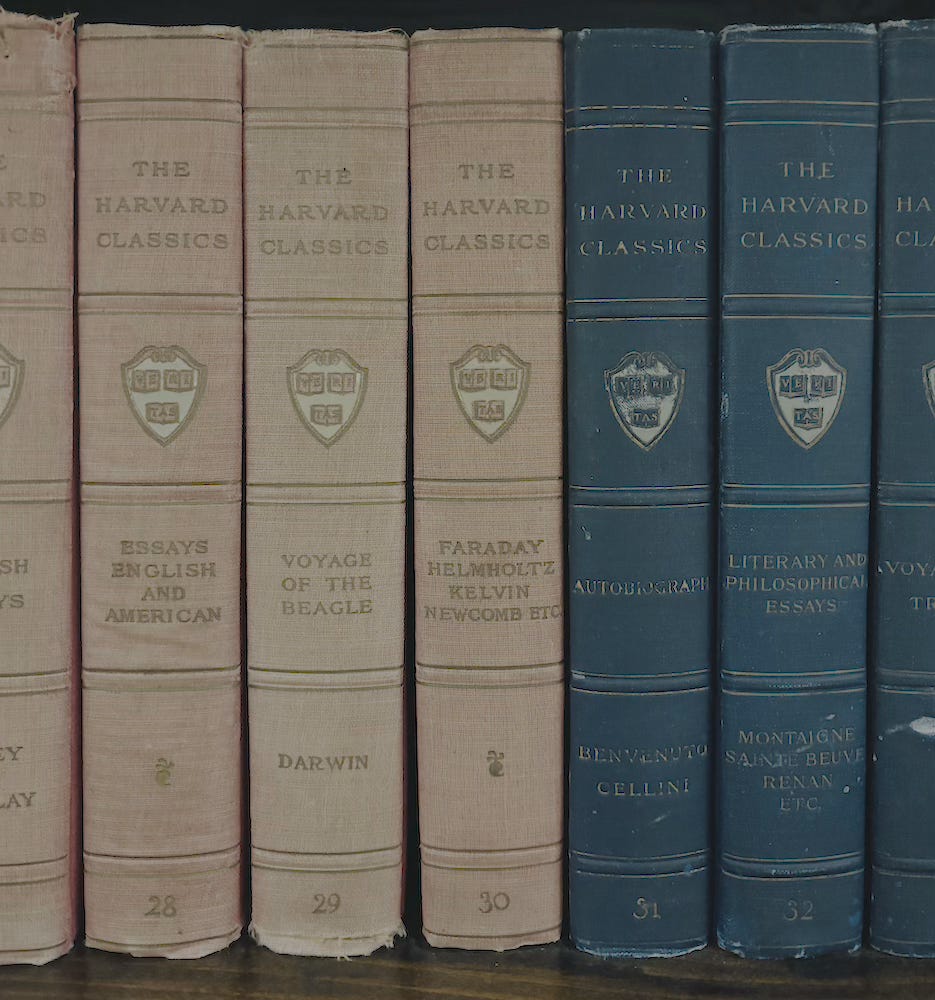

Sitting on a bookshelf in my living room are the fifty volumes of my great-grandfather's Harvard Classics. This series, first published in 1909-1910, was selected and edited by Harvard President Charles Eliot, not as an attempt to pick the “best books of all time”, as he put it, but rather “to give, in twenty-three thousand pages or thereabouts, a picture of the progress of the human race within historical times, so far as that progress can be depicted in books.” At the time the Harvard Classics came out, my great-grandfather was a young Latvian political refugee fleeing the violence of the 1905 Russian Revolution. He arrived in America in 1906 at the age of 19, and eventually became an accomplished bacteriologist at Merck Sharp & Dohme.

I never met him, but I suspect that my great-grandfather would have subscribed to Eliot's notion of human progress, progress that is the result of, as Eliot put it, “observing, recording, inventing, and imagining." The name “Harvard Classics” may sound pretentious today, but Dr. Eliot’s "five foot shelf of books" was mass-marketed to an American middle class that was presumed to share Eliot’s optimism about the trajectory of our civilization. The Harvard Classices were billed as a means by which, with just fifteen minutes of reading a day, anyone could gain access to the “prodigious store of recorded discoveries, experiences, and reflections which humanity in its intermittent and irregular progress from barbarism to civilization has acquired and laid up.” Since he owned these books, I presume my great-grandfather agreed with this general idea.

To describe what he was looking for in his selection of books, Eliot invoked the methods of science: “observing, recording, inventing, and imagining.” This is no accident — the Harvard Classics were released at a time when the modern scientific view of the world was arriving at a dominant position in our culture, carrying at least as much cultural heft as the major religions. In a cultural conquest as significant as the rise of major world religions in earlier centuries, science’s description of the world has become a near-universal baseline with which every other belief system, religious or not, is forced to reckon. Most items in the vast and surprising inventory of the scientific Big Picture—electrons, atoms, chromosomes, cells, galaxies, black holes, microwaves, mantle plumes, coronaviruses—are accepted as real by almost everyone, even though much of this inventory was unknown when my great-grandfather was born in 1887. (One striking example: scientists didn’t establish that there was more than one galaxy until the 1920’s.)

There is one volume in the Harvard Classics that most prophetically anticipates the coming cultural influence of scientific thought: Darwin's The Voyage of the Beagle. Too often, the Voyage is left out of Great Books lists in favor of Darwin’s more famous On the Origin of Species. The essayist Adam Kirsch, in an insightful piece on the Harvard Classics, chided Eliot for the excessive enthusiasm that led him to devote two of the fifty volumes to Darwin. Kirsch suggests that a modern edition of the Classics should "doubtless" keep On the Origin of Species and ditch the Voyage for James Watson's Double Helix. Darwin's Origin is often included in collections of great books by default, because it is one of the very few important primary scientific documents that can be read without specialized training. But if I had to pick one book by Darwin to recommend, it would be the Voyage. The Origin is an argument for a specific scientific theory. The Voyage is a much more general foreshadowing of science's cultural force in the modern world, written before science’s overwhelming presence in modern life was fully established.

Observations

The Voyage of the Beagle is Darwin's account of the five formative years abroad (1831-1836) with the crew of the HMS Beagle, an experience that transformed him into the scientist who would discover natural selection. The book was first published in 1839 as the most popular part of a multi-volume record of the Beagle's exploits, and later in 1845 as the definitive edition that we read today. The book is a hybrid, a scientific account fused to the ever-popular travel narrative. Darwin wrote both to summarize his scientific findings and to sell books to a reading public eager for accounts of exotic regions that most would never visit. The result is one of literature's great voyages, much like Moby Dick in its mass of scientific detail and similarly concerned with the meaning of nature and our place in it. What makes Darwin's Voyage stand out in this genre is his authentic, uncompromising scientific vision. Herman Melville in Moby Dick provides a stark contrast. While presenting pages and pages on the science and technology of whales and whaling, Melville agonizes over Providence, fate, purpose, and ultimate meaning in the universe. Darwin also has profound things to say about our place in the universe, but he does so without much fuss over the kinds of unanswerable questions that tormented Melville. Darwin patiently observes, records, and imagines, and in doing so sees a vast, complex planet that nevertheless can ultimately be explained.

Darwin's considerable powers of observation are immediately evident in The Voyage of the Beagle. His aim as a scientist is to infer the story underneath the visible events of nature, which is why he captures the small, but high-information details that allow him to narrow the space of possible explanations. Imagine arriving on the scene of the chaotic aftermath of a city devastated by an earthquake, with misery everywhere. While another writer might have written about human lives being subject to the whims of fate, here is Darwin on the 1835 earthquake that destroyed the Chilean city of Concepción:

The town of Concepción was built in the usual Spanish fashion, with all the streets running at right angles to each other; one set ranging south-west by west, and the other set north-west by north. The walls in the former direction certainly stood better than those in the latter; the greater number of the masses of brickwork were thrown down towards the north-east. Both these circumstances perfectly agree with the general idea of the undulations having come from the south-west; in which quarter subterranean noises were also heard; for it is evident that the walls running south-west and north-east which presented their ends to the point whence the undulations came, would be much less likely to fall than those walls which, running north-west and south-east, must in their whole lengths have been at the same instant thrown out of the perpendicular...

The different resistance offered by the walls, according to their direction, was well exemplified in the case of the Cathedral. The side which fronted the north-east presented a grand pile of ruins... The side walls (running south-west and north-east), though exceedingly fractured, yet remained standing; but the vast buttresses (at right angles to them, and therefore parallel to the walls that fell) were in many cases cut clean off, as if by a chisel, and hurled to the ground. Some square ornaments on the coping of these same walls were moved by the earthquake into a diagonal position.

Instead of chaos, Darwin sees geometry in the patterns in the surviving walls, down to the angles of the ornamental bricks. These patterns allow him to infer the behavior of the earthquake. It is this kind of observation and inference that eventually leads to the capacity to build more earthquake-resistant buildings.

Here is Darwin observing a wasp hunting a spider:

The wasp made a sudden dash at its prey, and then flew away: the spider was evidently wounded, for, trying to escape, it rolled down a little slope, but had still strength sufficient to crawl into a thick tuft of grass. The wasp soon returned, and seemed surprised at not immediately finding its victim. It then commenced as regular a hunt as ever hound did after fox; making short semicircular casts, and all the time rapidly vibrating its wings and antennae. The spider, though well concealed, was soon discovered, and the wasp, evidently still afraid of its adversary's jaws, after much manoeuvring, inflicted two stings on the under side of its thorax. At last, carefully examining with its antennae the now motionless spider, it proceeded to drag away the body.

Darwin notes where and how often the spider has been stung, and discovers the rationale behind the wasp's motion that others might have taken to be a random walk. Driving Darwin's method is a belief that the world has an underlying rationale, one that can be inferred if we look closely enough. The behavior of wasps and spiders is not unfathomable; it is a careful survival strategy. Earthquakes don't randomly knock down walls; they travel in waves and exert forces on buildings at particular angles. Darwin's observations are precise because the world is precise, locked into tight constraints of cause and effect, and therefore we use the tools of reason and observation to understand why the world behaves the way it does.

Darwin showed a disciplined commitment to avoiding unjustified shortcuts in the pursuit of answers. Curiosity may be a common human trait, but rigorously and reliably satisfying that curiosity is not. Darwin often had difficulty convincing people that he was genuinely driven to understand the workings of nature, and that he wasn't secretly prospecting for valuable ores:

I found the most ready way of explaining my employment was to ask them how it was that they themselves were not curious concerning earthquakes and volcanos?--why some springs were hot and others cold?--why there were mountains in Chile, and not a hill in La Plata? These bare questions at once satisfied and silenced the greater number; some, however (like a few in England who are a century behindhand), thought that all such inquiries were useless and impious; and that it was quite sufficient that God had thus made the mountains.

Science depends upon a restless, intellectual dissatisfaction with inadequate, speculative answers. It was this dissatisfaction that drove Darwin to brave thousands of miles while enduring discomforts, seasickness, earthquakes, severe thirst, cold nights on beds of rocks, vile food, and even violent political upheaval, with an energy that is evident on every page of the Voyage.

People

It would be wrong to assume that Darwin's scientific instincts make him a passionless observer of the world. In fact, much of the power of the Voyage comes from Darwin's capacity to find emotional resonance in the targets of his scrutiny. His knack for seeing precisely works with his sense of humanity to make Darwin particularly skilled at rendering people, and describing their poignant and ironic moments as they respond to their natural and social environments.

This is perhaps most vividly seen in Darwin's account of his encounters with the natives at the end of the world in Tierra del Fuego. The crew of the Beagle, on a previous voyage, had basically kidnapped several Fuegians, and the Beagle's captain was bringing them back home. One of these natives, 'Jemmy Button', was purchased as a boy for the price of a pearl button. Now a young man, he is about to return to his stone age culture, after having spent three years within one of the world's most technologically sophisticated civilizations. He hardly remembers his native language and speaks broken English, but, like any teenager, is very impressed with the fact that he can make himself look sophisticated:

Jemmy was short, thick, and fat, but vain of his personal appearance; he used always to wear gloves, his hair was neatly cut, and he was distressed if his well-polished shoes were dirtied. He was fond of admiring himself in a looking glass; and a merry-faced little Indian boy from the Rio Negro, whom we had for some months on board, soon perceived this, and used to mock him: Jemmy, who was always rather jealous of the attention paid to this little boy, did not at all like this, and used to say, with rather a contemptuous twist of his head, “Too much skylark.”

Jemmy is struggling with acute and ambiguous feelings about his background: he is defensive about his people, yet he wants to prove that despite his family roots, he can be at least as civilized as any of his British shipmates. And now he's about to be unceremoniously dropped back among his kinfolk. In the mid-nineteenth century, too many thought nothing of such callous treatment; for them, there was a natural order to things, and Jemmy was best off in his proper place. But Darwin manages, almost inadvertently, to poignantly render the ambiguity of Jemmy's reunion with his family:

We had already perceived that Jemmy had almost forgotten his own language. I should think there was scarcely another human being with so small a stock of language, for his English was very imperfect. It was laughable, but almost pitiable, to hear him speak to his wild brother in English, and then ask him in Spanish ("no sabe?") whether he did not understand him.

Some time later, when the Beagle briefly returns to the region before leaving for good, Jemmy shows up again in a canoe, unclothed, scrawny, and long-haired. His first action is to turn his back on his former shipmates in embarrassment.

Darwin's account of the Fuegians is unforgettable because Darwin was more unsettled by his encounters with these people than with any others during his five year voyage. He is honest about his rattled feelings and about the difficulty he has making sense of what appear to him to be lives of unnecessary misery:

A woman, who was suckling a recently-born child, came one day alongside the vessel, and remained there out of mere curiosity, whilst the sleet fell and thawed on her naked bosom, and on the skin of her naked baby! These poor wretches were stunted in their growth, their hideous faces bedaubed with white paint, their skins filthy and greasy, their hair entangled, their voices discordant, and their gestures violent. Viewing such men, one can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world. It is a common subject of conjecture what pleasure in life some of the lower animals can enjoy: how much more reasonably the same question may be asked with respect to these barbarians! At night five or six human beings, naked and scarcely protected from the wind and rain of this tempestuous climate, sleep on the wet ground coiled up like animals. Whenever it is low water, winter or summer, night or day, they must rise to pick shellfish from the rocks; and the women either dive to collect sea-eggs, or sit patiently in their canoes, and with a baited hair-line without any hook, jerk out little fish. If a seal is killed, or the floating carcass of a putrid whale is discovered, it is a feast; and such miserable food is assisted by a few tasteless berries and fungi.

Putting ourselves in Darwin’s place, if we were confronted with such people who seemed thoroughly alien, but are nonetheless as human as anyone else in their intelligence, their desires, and their needs, how would we react? In this case, Darwin's method of observing and then inferring the story again serves him well, because he does not try to fit the Fuegians into some morality tale. Instead, recognizing them as fully human, he attempts to understand how it could be that they exist in such an apparently miserable condition.

[O]ne asks, Whence have they come? What could have tempted, or what change compelled, a tribe of men, to leave the fine regions of the north, to travel down the Cordillera or backbone of America, to invent and build canoes, which are not used by the tribes of Chile, Peru, and Brazil, and then to enter on one of the most inhospitable countries within the limits of the globe? Although such reflections must at first seize on the mind, yet we may feel sure that they are partly erroneous. There is no reason to believe that the Fuegians decrease in number; therefore we must suppose that they enjoy a sufficient share of happiness, of whatever kind it may be, to render life worth having. Nature by making habit omnipotent, and its effects hereditary, has fitted the Fuegian to the climate and the productions of his miserable country.

Language

Darwin is a scientific stylist, writing a travel narrative that shows how the practice of science is not an impersonal, algorithmic process, but is instead a human act of imagination. The Voyage shows, at the fine level of sentences and paragraphs, a scientific imagination churning away, observing, sifting, and finally inferring the story of nature's driving forces. As Darwin puts it, “The limit of man's knowledge in any subject possesses a high interest, which is perhaps increased by its close neighbourhood to the realms of imagination.”

In this, Darwin compares favorably with another first-rate travel writer, Herman Melville. Both Darwin and Melville cut their teeth producing best-selling accounts of their voyages to the Southern hemisphere. (In Melville's case the accounts were lightly fictionalized.) Both knew what would sell among the travel-narrative-reading public, but the differences in their styles highlight the power that Darwin's scientific instincts bring to his language.

Melville's imagery is impressionistic, as in this description of the Galapagos from The Encantadas:

In many places the coast is rock-bound, or, more properly, clinker-bound; tumbled masses of blackish or greenish stuff like the dross of an iron-furnace, forming dark clefts and caves here and there, into which a ceaseless sea pours a fury of foam; overhanging them with a swirl of gray, haggard mist, amidst which sail screaming flights of unearthly birds heightening the dismal din. However calm the sea without, there is no rest for these swells and those rocks; they lash and are lashed, even when the outer ocean is most at peace with, itself. On the oppressive, clouded days, such as are peculiar to this part of the watery Equator, the dark, vitrified masses, many of which raise themselves among white whirlpools and breakers in detached and perilous places off the shore, present a most Plutonian sight. In no world but a fallen one could such lands exist.

Darwin, while also drawing a comparison with iron-foundries, doesn’t make vague observations about "blackish and greenish stuff." His imagery depends on observational precision and tight organization of his thoughts. His words, while not always technical, are usually specific, and descriptions are often given in geometrical terms of symmetries, regularities, lines, and circles. Here is Darwin on Chatham Island:

The entire surface of this part of the island seems to have been permeated, like a sieve, by the subterranean vapours: here and there the lava, whilst soft, has been blown into great bubbles; and in other parts, the tops of caverns similarly formed have fallen in, leaving circular pits with steep sides. From the regular form of the many craters, they gave to the country an artificial appearance, which vividly reminded me of those parts of Staffordshire where the great iron-foundries are most numerous. The day was glowing hot, and the scrambling over the rough surface and through the intricate thickets was very fatiguing; but I was well repaid by the strange Cyclopean scene. As I was walking along I met two large tortoises, each of which must have weighed at least two hundred pounds: one was eating a piece of cactus, and as I approached, it stared at me and slowly walked away; the other gave a deep hiss, and drew in its head. These huge reptiles, surrounded by the black lava, the leafless shrubs, and large cacti, seemed to my fancy like some antediluvian animals.

Another strategy that Darwin uses to powerful effect is the shocking contrast between violence and beauty so commonly found in the world. In this case, the murder of a sea captain intrudes on a serene moment in the Galapagos:

The water is only three or four inches deep and rests on a layer of beautifully crystallised, white salt. The lake is quite circular, and is fringed with a border of bright green succulent plants; the almost precipitous walls of the crater are clothed with wood, so that the scene was altogether both picturesque and curious. A few years since the sailors belonging to a sealing-vessel murdered their captain in this quiet spot; and we saw his skull lying among the bushes.

Note that the lake is not fringed with generic green plants, but green succulent plants. The walls of the crater are "almost precipitous"; here precipitous means literally perpendicular, forming a 90 degree angle with the surface. And contrasting with this very specific, orderly scene is a messy reminder of human conflict.

God

In the early 17th century, Francis Bacon warned that “from [an] unwholsome mixture of things human and divine there arises not only a fantastic[al] philosophy but also a heretical religion.” It’s a warning that scientists have taken seriously ever since. Darwin, in all of his arguments, inferences, hypotheses, and narratives of natural history, quietly refuses to ever invoke God as an explanation. The geographical distribution of animals, the causes of extinctions, the composition of mountain ranges, the layout of the plains of the South American Pampas, are all explained exclusively in terms of natural processes. These processes operate over vast scales of space and time, and are thus often not directly observable. They are inferred from observable evidence: raised beds of fossilized sea shells, thousands of miles from any ocean; folded layers of various types of rock exposed in the great mountains of the Cordillera; the resemblance of the skeletons of long-extinct, gigantic quadrupeds to those of living species. It is by inferences made from observations like these that Darwin and many others developed the grand explanations of the origin of the world around us, explanations that have now thoroughly infiltrated and in many cases completely supplanted those provided by other systems of belief.

Here is Darwin inferring a thoroughly materialistic creation story of the great mountain ranges of the South American Cordillera:

As the beds of the conglomerate have been thrown off at an angle of 45 degrees by the red Portillo granite (with the underlying sandstone baked by it), we may feel sure that the greater part of the injection and upheaval of the already partially formed Portillo line took place after the accumulation of the conglomerate, and long after the elevation of the Peuquenes ridge. So that the Portillo, the loftiest line in this part of the Cordillera, is not so old as the less lofty line of the Peuquenes. Evidence derived from an inclined stream of lava at the eastern base of the Portillo might be adduced to show that it owes part of its great height to elevations of a still later date. Looking to its earliest origin, the red granite seems to have been injected on an ancient pre-existing line of white granite and mica-slate.

The Voyage makes it clear that scientists' refusal to invoke divine agency as a causal explanation does not arise from an innate or personal opposition to religion. At issue is what suffices as an explanation. Darwin refuses to settle for vagueness, and rightly considers statements like 'it was born in nature', or 'God made it' to be no better (or perhaps worse) than saying 'I don't know.' This refusal to accept the unfathomable as an explanation is the first step in the scientific process, and it clears the ground for observation, hypothesis, inference, and experiment to operate. It is based on a belief that the world, unlike God, is not inscrutable, and that our minds can comprehend the detailed links of cause and effect that happen behind the scenes of the everyday, observable world. What you read in the Voyage is an almost fanatical demand for precision and rigor, a curmudgeonly insistence that we don't fill in our stories with what scientists call 'hand waving.' Again and again Darwin rejects such hand-waving, content-free explanations.

Of petrified trees:

How surprising it is that every atom of the woody matter in this great cylinder should have been removed and replaced by silex so perfectly that each vessel and pore is preserved! These trees flourished at about the period of our lower chalk; they all belonged to the fir-tribe. It was amusing to hear the inhabitants discussing the nature of the fossil shells which I collected, almost in the same terms as were used a century ago in Europe,--namely, whether or not they had been thus "born by nature."

Boiling water:

At the place where we slept water necessarily boiled, from the diminished pressure of the atmosphere, at a lower temperature than it does in a less lofty country; the case being the converse of that of a Papin's digester. Hence the potatoes, after remaining for some hours in the boiling water, were nearly as hard as ever. The pot was left on the fire all night, and next morning it was boiled again, but yet the potatoes were not cooked. I found out this by overhearing my two companions discussing the cause, they had come to the simple conclusion "that the cursed pot (which was a new one) did not choose to boil potatoes."

Today, scientific explanations of the world are overwhelmingly what we teach and what we research, and it is these exaplanations on which we base our technologies, our medical practice, and much of our social and and economic organization. This was not yet true when Darwin was writing his travel narrative, but the eventual cultural success of science was probably inevitable. Galileo, Newton, and their 17th century colleagues invented a method, rooted in extremely precise observation and careful inference, to reliably learn about the world. Three centuries of steady growth in reliable knowledge brought about the most astonishing material transformation of human life in the history of our species. By the time of the Voyage, science was making serious inroads into matter and earth's history, and it was about crack open biology in a spectacular way.

My great-grandfather, during his career as a bacteriologist, witnessed the first great taming of infectious disease by the development of antibiotics and new vaccines. Within the past few years, scientists have made the first direct observation of a black hole, invented new therapies to treat disease by editing a patient’s DNA, and built AI that can write code and design proteins. One hundred eighty years after the publication of the Voyage, science is a relentless current in our society whose power can be compared with the streams that Darwin observed in the Chilean Cordillera:

As often as I have seen beds of mud, sand, and shingle, accumulated to the thickness of many thousand feet, I have felt inclined to exclaim that causes, such as the present rivers and the present beaches, could never have ground down and produced such masses. But, on the other hand, when listening to the rattling noise of these torrents, and calling to mind that whole races of animals have passed away from the face of the earth, and that during this whole period, night and day, these stones have gone rattling onwards in their course, I have thought to myself, can any mountains, any continent, withstand such waste?

Pick up a free, electronic copy of The Voyage of the Beagle over at Project Gutenberg. (http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3704)

This essay is adapted from a much earlier piece published at my old blog, The Finch & Pea.